Artist and Vivian Maier biographer Pamela Bannos uses ‘forensic’ research skills to find what’s hidden

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but for “investigative artist” Pamela Bannos images might also be measured in archaeological terms — shovelfuls, perhaps. The Northwestern professor of instruction in Art, Theory, and Practice has a passion for excavating well below the surface to reveal connections between past and present, the overt and hidden, and the intended and (re)imagined.

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but for “investigative artist” Pamela Bannos images might also be measured in archaeological terms — shovelfuls, perhaps. The Northwestern professor of instruction in Art, Theory, and Practice has a passion for excavating well below the surface to reveal connections between past and present, the overt and hidden, and the intended and (re)imagined.“Detective and forensic-type work is fascinating to me,” says Bannos, a Chicago native who came into the arts “via a side door,” after earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology and sociology and then an MFA in photography.

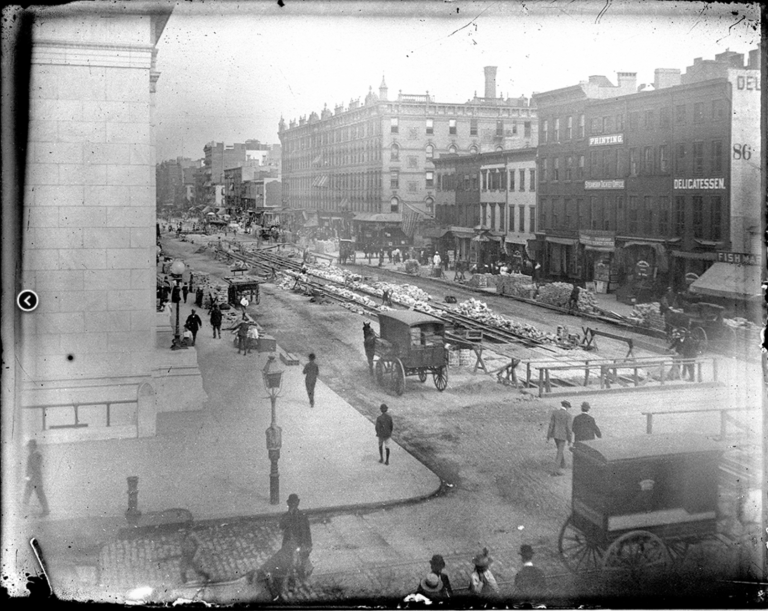

An avid collector — she owns about 300 cameras — Bannos has always been curious about “how objects and places carry their history,” an interest that has informed her various site-based projects that merge historical research with art and artistic presentation. Her year-long research effort for “8th Avenue at 14th Street” began with an unmarked box of 20 glass negatives bought from an online auction. One image, the eponymous New York street corner, became the basis for Bannos’ web project that demonstrated what each part of the image revealed and shared everything that the New York Times reported having happened within the area of the photograph. She included a history of the tenants in each building depicted as well as her own street photos and a video she created within the space of the original negative.

“Investigative artist” Pamela Bannos, associate professor of instruction in art theory and practice, brings formidable research skills to her work, including her celebrated biography of photographer Vivian Maier.

“Investigative artist” Pamela Bannos, associate professor of instruction in art theory and practice, brings formidable research skills to her work, including her celebrated biography of photographer Vivian Maier.Bannos says the project “investigated the mostly invisible layers of history” and led to similar site-based projects in Chicago, such as Hidden Truths, a study of Lincoln Park’s undocumented past, and Shifting Grounds, which explored the history and site of the Museum of Contemporary Art. Because of her archaeologically-inspired online visualizations of the sites, she’s been called a “meta-photographer,” and the research has crossed over into other fields, including urban history. Bannos embraces this expanded identity and its possibilities. Too often, she says, people seem “stuck” in an antiquated way of thinking about what art is and what artists do. “I am interested in the process of discovery. My art practice extends to the presentation of my research through websites and artist talks,” she says.

Art and Inquiry

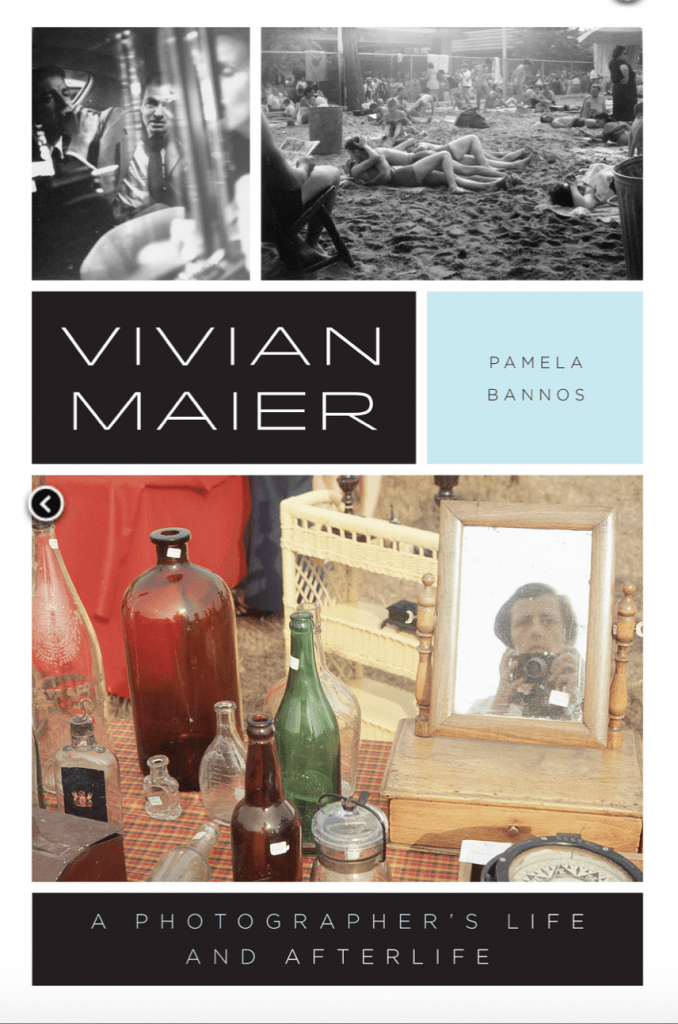

Pamela Bannos’ meticulously researched 2017 biography of photographer Vivian Maier also offers a showcase for the author’s revelatory talent and ability to combine her disparate expertise.

Pamela Bannos’ meticulously researched 2017 biography of photographer Vivian Maier also offers a showcase for the author’s revelatory talent and ability to combine her disparate expertise.Bannos’ meticulously researched 2017 biography of photographer Vivian Maier also offers a showcase for the author’s revelatory talent and ability to combine her disparate expertise. The book has earned acclaim for demystifying a prodigiously gifted but guarded figure — the “North Shore nanny with a camera,” as the caricature goes — whose legacy had been shaped largely by those who assumed control of her archives at auction in 2007, two years before Maier’s death. That Maier never courted much notice, let alone fame, hasn’t stopped posthumous media attention, including books, gallery exhibitions, and an Academy Award-nominated documentary, Finding Vivian Maier(2014).

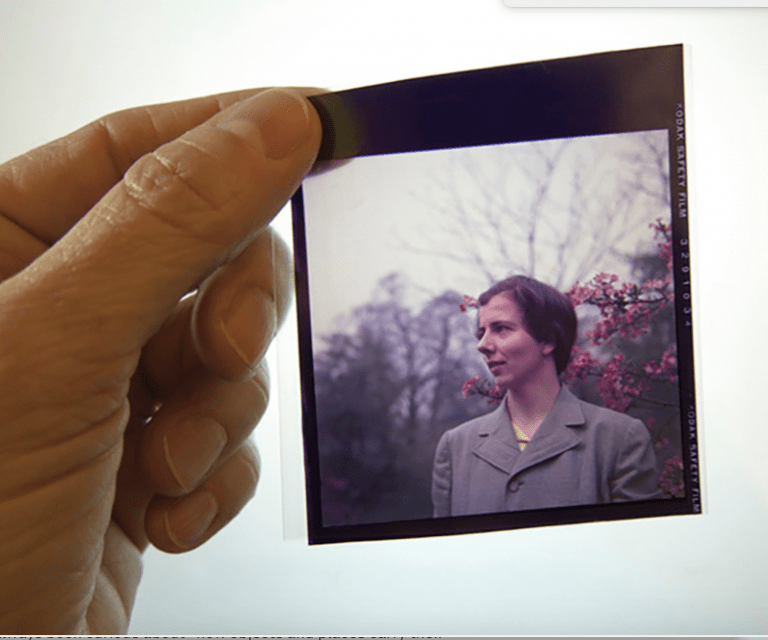

Bannos, though, found a markedly different character through her intensive study of what she calls Maier’s “fractured archive.” Rather than the ghostly presence often depicted elsewhere, Maier comes across as a flesh-and-blood person in Bannos’ “counternarrative.” The book is the culmination of a five-year research project that examined tens of thousands of images, including scrutinizing geographic or technical details, and retracing many of Maier’s steps to gain new understanding of a woman whose cultivated anonymity obscured her artistry during her lifetime. In fact, that Maier never intended her work to be shown publicly is one of the compelling ethical considerations that Bannos addresses.

“My goal was to give her story back to her, and to tell it as correctly as possible,” says Bannos, who has taught photographic theory and practice at Northwestern for 24 years, including the course “On Seeing and Believing,” which surveys imagery’s historical “capacity for misrepresentation.”

Picturing Truth

A year-long research effort for Bannos’ site-based project “8th Avenue at 14th Street” began with an unmarked box of 20 glass negatives bought from an online auction. One of those images became the touchstone for an exhaustive exploration of the details photographed.

A year-long research effort for Bannos’ site-based project “8th Avenue at 14th Street” began with an unmarked box of 20 glass negatives bought from an online auction. One of those images became the touchstone for an exhaustive exploration of the details photographed.In an image-saturated world, the truth isn’t always obvious; the apparent can hide as much as it reveals, especially when willfully manipulated. Our eyes are out-maneuvered and fatigued by the visual torrent: On Instagram alone, 800 million active monthly users post an estimated 95 million photos and videos each day. Even before the digital era, the photograph presented special challenges, and still does. The relationship of the moment captured in the frame to the moment that came immediately before or after the camera shutter’s activation remains mysterious. Perhaps that’s part of photography’s allure — its power to summon a frozen moment from eternity. The circumstances present fascinating aesthetic, philosophical, and research questions that Bannos explores.

“I’m interested in the line between truth and fiction,” she says, referencing a framework that has informed her projects such as “Some Untitled Pictures,” a collection of found vintage snapshots, many from European flea markets, that Bannos has digitally manipulated. Sometimes she will isolate a seemingly unintended element or otherwise try to “look past the obvious or reveal the layers in an image” that are not always immediately apparent. She says this process sometimes “redefines” things that are already in the photograph and points out the “fluid nature of ‘truth’” in the frame: “Gazes, gestures, and relationships between people become more pronounced when they may have been fleeting or unintended.”

Bannos credits her father’s wide-ranging interests in helping to shape her curiosity and intellectual development. The son of Greek immigrants, her father owned a diner and was involved in various other endeavors, indulged in these pursuits by his wife, a grade-school teacher and the only family member of her generation to earn a college degree.

“He was curious about all cultures and was a collector of everything from Italian porcelains to African bronzes,” Bannos says of her father. “He was a black belt judo instructor and a Shrine clown. He was also a sculptor of realistic bronze busts. We went to judo matches, parades, the circus, and Chicago art exhibitions during the age of ‘happenings.’ It made for a slightly surreal childhood.”

Photography’s future continues to change, partly in response to technology. The acceleration in how we make and share images has a host of implications, including our expectations about those images and our relationship to them, Bannos says.

“Photography has become ephemeral. There are no more paper snapshots,” she says. Yet, the era of digital imaging has created a strange permanence, too, with vast online archives and social media documenting the current generation in an unprecedented way.

For Bannos, the best art can still surprise and make us think, see, or understand in ways we may not have previously considered, and can inform many other areas of discovery. She recalls participating in a 2001 collaboration with a professor from the Department of Physics and Astronomy that culminated in an exhibition at Northwestern’s Block Museum. Imaging and Imagining Space, featured visible, invisible, and imagined black-and-white photographs produced by various telescopes and purely invented in the photographic darkroom.

“What I found most fascinating about the exhibition was that in the guise of ‘Science’ people believe photographs,” says Bannos. “The authority of the scientist seems to make images factual.” Her favorite recollection occurred at the exhibition’s opening, when an astronomer tried to explain one of Bannos’ own darkroom photographs to her, pointing out the various “star-like” features.

“He was entirely perplexed when I insisted that the image depicted spray paint on glass.”